Weed on the crater: What can the history of deglobalisation teach us about organisations in Poland?

Abstract

This article explores deglobalization’s historical and contemporary dynamics, focusing on its implications for organizational design in Poland. It argues that deglobalization, characterized by the instability of financial systems, protectionism, and hostility towards migration, is a cyclical phenomenon driven by globalization itself. The chapter examines how Poland’s peripheral position and historical discontinuities have shaped its organizational responses, including ephemeral entities in the immediate aftermath of World War I to large state-owned projects. It concludes by contemplating future organizational strategies amidst ongoing global shifts, emphasizing the importance of resilience and adaptability.

DOI: 10.48285/ASPWAW9788366835788PL

We live in times of deglobalisation, understood as a process of limiting integration and cooperation between the world’s countries and institutions. The COVID-19 pandemic, mass migrations, natural disasters caused by climate change, a vision of economic recession and military conflicts – all these phenomena contribute to increasing distrust and an ever-greater concentration on national interest. Deglobalisation often comes hand in hand with the dissolution of empires and the ancien regime – a process that sometimes takes on the form of revolutions or wars and can take many decades. The current war in Ukraine can, in fact, be considered a war by the Russian Empire to maintain its influence in areas that the said empire considers its sphere of interest. On the other hand withdrawal of the US coalition forces from Afghanistan, reminiscent of the evacuation of British colonial forces in the 19th century, or the 1987 pull-out of Soviet troops just before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The political, epidemic and climate-related shocks experienced in recent years have resulted in an increased interest in the topics of resilience and designing shock-resistant organisations, both in academic papers as well as in mainstream media. Some more visionary authors like Nassim Taleb have recently popularised the somewhat hazy term ‘antifragile’, thus arguing for the design of organisations that grow owing to shocks they experience. 1 1 N. N. Taleb, Antifragile. Things that Gain from Disorder, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, London 2014. ↩︎ Meanwhile, in Poland, there is an old saying: ‘makeshift is the most durable’, while the expression ‘weed on the crater,’ cited in the title and taken from Melchior Wańkowicz’s novel 2 2 M. Wańkowicz, Ziele na kraterze, PAX, Warsaw 1957 [English edition: New York 1951]. ↩︎, where it serves as a metaphor for the sinister impermanence of the Polish reality. Therefore, the question arises how should we design organizations in times of impermanence – organizations that are resistant to shocks, or perhaps rather temporary, unstable, ephemeral organizations?

To answer this question, it is first necessary to understand the origins of the differences in approaches to organizational design. For this purpose, it is worth first taking a look at the course of deglobalization that took place 100 years ago and, on this basis, try to draw conclusions for the design of organizations in Poland.

How to recognise deglobalisation?

Business historians describe deglobalisation as a periodic political, social and economic phenomenon. Three main factors that characterise deglobalisation are: 1. the instability of financial systems; 2. the collapse of global trade and the rise of protectionism; 3. the decline of universalist philosophy and a hostility against migrations. 3 3 See e.g.: G. Jones, Multinationals and global capitalism: From the nineteenth to the twenty first century, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005; H. James, The end of globalization: lessons from the Great Depression, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, London 2009; A. Colli, Dynamics of international business: Comparative perspectives of firms, markets and entrepreneurship, Routledge, London, New York 2015; V. Binda, A. Colli, Globalization: A Key Idea for Business and Society. Taylor & Francis, London, New York 2024. ↩︎ Thus defined, deglobalisation is, paradoxically, a result of globalisation. An increased number of global financial relations leads to the increased instability of the financial system due to a heightened risk and as a result of the scale and scope of disruptions in case of crisis. On the other hand, the development of global trade results in imbalances and inequalities; it increases protectionist tendencies and the risk of customs wars. Lastly, as a result of international migrations, a mass culture clash takes place and serves as catalyst for xenophobia, racism and nationalism.

On this occasion, it is important to recall the warnings made by historians against our misleading belief in technological progress and in international corporations, seen as forces able to prevent deglobalisation. 4 4 G. Jones, op. cit. ↩︎ History has proven that both technology and the interests of international corporations have usually rather accelerated and reinforced the process. At the turn of the 20th century, new technologies were used in the arms race, with the press and the nascent media being used to spread propaganda, and with the latest achievements in transport and communication not only deteriorating the epidemic situation, but eventually being used in the global conflict of WW2. We see the echoes of these troubling phenomena in the contemporary destabilisation of the financial markets by cryptocurrencies, the customs wars triggered by e-commerce and global logistics, and the sprawl of nationalism and terrorism via social media.

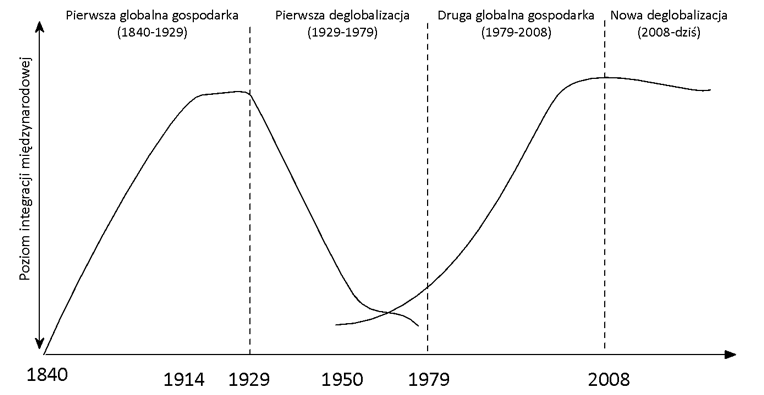

Deglobalisation is thus an inevitable, cyclical, long-duration process, meaning that its occurrence can be observed and understood only in a long-term perspective. 5 5 F. Braudel, I. Wallerstein, History and the social sciences: the longue durée, “Review (Fernand Braudel Center)” Vol. 32(2)/2009, p. 171–203. ↩︎ The graph below roughly illustrates this by showing the most recent period of the global economy and its disintegration.

Source: based on G. Jones, 2005.

As the graph depicts, the previous period of deglobalisation took place almost a hundred years ago. Its beginning coincided with the end of World War 1 and, apart from climate change, was accompanied by similar circumstances, i.e. mass migrations, pandemics, a financial crisis and a radical surge in nationalism. From our perspective, the most important was the initial moment and the side-effect of deglobalisation – the disintegration of three empires: Prussia, Austro-Hungary and Russia. Their decay, by a fortunate coincidence, led to the rebirth of the Poland, which, in an era of deglobalisation, immediately proceeded to design organisations and institutions necessary for the correct functioning of the state.

Deglobalisation from the perspective of the centre and the peripheries

Before we proceed to reflect on the history of organisation design in Poland during the interbellum period, it is important to answer the key question: where do we stand in the deglobalisation process – in the centre, or at the peripheries? 6 6 I. Wallerstein, World-systems analysis: An introduction, Duke university Press, 2020. ↩︎ Depending on how we answer, the experiences and the challenges behind organisation design will be entirely different. An example of this can be found in a fragment of the memoirs of the Austrian author, Stefan Zweig, entitled The World of Yesterday: Memoires of a European, representing the motif of deglobalisation from a perspective of Viennese citizen:

I was born in 1881 in a great and mighty empire, in the monarchy of the Habsburgs. But do not look for it on the map; it has been swept away without trace. I grew up in Vienna, the two-thousand-year-old supernational metropolis, and was forced to leave it like a criminal before it was degraded to a German provincial city. (…) Everything in our almost thousand-year-old Austrian monarchy seemed based on permanency, and the State itself was the chief guarantor of this stability. The rights which it granted to its citizens were duly confirmed by parliament, the freely elected representative of the people, and every duty was exactly prescribed. Our currency, the Austrian crown, circulated in bright gold pieces, an assurance of its immutability. (…) From the standpoint of reason the most foolish thing I could do after the collapse of the German and Austrian arms was to go back to Austria, that Austria which showed faintly on the map of Europe as the vague, gray and inert shadow of the former Imperial monarchy. (…) [T]he industries which had formerly enriched the land were on foreign soil, the railroads had become wrecked stumps, the State Bank received in place of its gold the gigantic burden of the war debt. 7 7 S. Zweig, The World of Yesterday. An Autobiography by Stefan Zweig, The Viking Press, New York 1943, p. xviii – 1, 281. ↩︎

The above excerpt describes deglobalisation from the perspective of the centre and expresses the author’s surprise at the fragility of the state system, blended with nostalgia and sadness relating to the gradual loss of importance of long-established institutions. However, it is important to underline – against the author’s intentions – that institutions such as the railroads and the Austrian national bank, and even some of the industries that “were on foreign soil”, survived that period of deglobalisation and still exist today. Therefore, from the central perspective, deglobalisation has been linked to a sudden and significant reduction in the scale, range and prestige of organisations, but not to their disintegration or loss of continuity. Consequently, designing organisations in the centre will be related to redesigning, descaling, and restructuring and increasing resilience of existing organizations against future shocks.

Meanwhile, the challenges resulting from deglobalisation in Poland look entirely different, as illustrated by an excerpt from the preface of Ksiega Dziecieciolecia Polski Odrodzonej (Poland Reborn: Centenary Book, 1928) by Jan Rozwadowski, then-chair of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences and professor of the Jagiellonian University:

So we will look at the image of the decade and feel that this is the image and the result of our work – of all of us; work that we’ve done despite all the moaning – both our own and foreign. But let us remember about two things. First, about what was there in 1918, i.e. that only in the Lesser Poland region was there any administration, schooling, judiciary, treasury, post, railroads etc. organised somehow. In other regions, all this was alien. Then, even in Lesser Poland, the military and the gendarmerie were foreign, and that all other authorities, apart from the autonomous ones, were introduced top-down. Then, we must remember that the whole country was, apart from the Western part of Kresy [borderlands], destroyed by war and utterly shocked, and that not only were we burdened with internal social issues, but also by our fight with Ukrainians, and soon after our war with Russia, and that amidst this chaos, we needed to instantly organise and launch, almost from scratch, an entire public life machine. 8 8 Dziesięciolecie Polski Odrodzonej. Księga pamiątkowa 1918–1928 [Poland Reborn: Centenary Book 1918–1928], introduction: J. Rozwadowski, Wydawnictwo “Ilustrowanego Kuryera Codzienego”, “Światowida”, “Na szerokim świecie”, Kraków, Warszawa 1928, p. 12. ↩︎

As this quote indicates, the main challenge for the reborn country was not restructuring, but building an entirely new institutional and organisational system. The difference lies mainly in Poland’s peripheral position in the deglobalisation process. In the times of peace and globalisation, this was an area of risky but lucrative investments, where an affordable local workforce and weak regional administration offered unique opportunities. During wartime, however, this was an area where movements of military fronts drained both human resources as well as the local economy. Finally, it was an area from which, in the case of defeat, each of the central powers (Russia, Prussia, Austria) evacuated the remaining capital, people and hardware deep into to their territories. As a result, after regaining independence, Poland was drained of capital, human resources, and technology. Industry and firms needed to recover using the remains of the capital and infrastructure that was left behind, and the previously existing crucial institutional and trade relationships with the three former centres were broken. The country was facing several challenges: from wars that were to define its borders, to poverty, famine and illiteracy, as well as political, economic and health-related crises. Contemporary commentators dubbed Poland a “seasonal state” (Ger. Saisonstaat) – a buffer state in their relations with now-Soviet Russia. 9 9 G. L. Weinberg, Germany, Hitler, and World War II: essays in modern German and world history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1996. ↩︎ The main challenge for designing organisations on the peripheries was thus “building from scratch”, and the scale of threats and humanitarian challenges required immediate and effective solutions.

Between ephemerals and state: organisation design in the peripheries

So what did organisation design look like 100 years ago in Poland, in the context of the progressing deglobalisation and the problems of the periphery? Similarly to the periodisation adopted by economic historians, the interwar era can be divided into three periods, dominated by three types of organisation: 1) the reconstruction period, dominated by ephemeral domestic organisations; 2) the crisis period dominated by foreign investments; and 3) the state interventionism period, dominated by state-owned enterprises and statism.

In the first period, the scale of the challenges significantly outgrew the modest capabilities and resources of the newly created Polish state. At the same time, Poland’s image as a “seasonal state”, the wars conducted on its borders, and the threat of a Bolshevik invasion discouraged any direct involvement of foreign capital in the reconstruction process. The Polish government and entrepreneurs had to rebuild organisations by their own strength, making use of what the former partitioners had failed to take back to their respective centres. The initial results of the research conducted on interwar stock companies point to an interesting phenomenon: an explosion in founding and registering companies in the years 1918–1920, i.e. right after World War 1. Data reveals that, despite the seeming hopelessness of the situation in the deglobalised sphere of the ‘seasonal state’, entrepreneurs and local communities took up various initiatives aimed at reconstructing the country. Considering the context of their emergence, their limited resources and impermanence, these initiatives can be seen as ephemeral. 10 10 G. F. Lanzara, Ephemeral organizations in extreme environments: Emergence, strategy, extinction [I], “Journal of Management Studies,” vol. 20/1983, p. 71–95. ↩︎ Such organisations usually emerge during natural disasters and solve problems ad hoc. Their structure is mostly horizontal, informal and flexible, and they often make use of creativity and improvisation to obtain essential resources. 11 11 Ibid. ↩︎ Their biggest disadvantage is their limited scale, impermanence, short operational period and the fact that they can easily be replaced by more stable and attractive alternatives. This is exactly what happened to ephemeral organisations in the second phase of the reconstruction when they were gradually substituted by foreign capital, and experienced mass bankruptcies in the first phase of the 1929 economic crisis.

In the second period, the Polish state won the war with the Bolsheviks and managed to stabilise its borders. Paradoxically, the military coup in May 1926 contributed to the stabilisation of the internal political system. Functioning in a permanent crisis and under a constant threat to its existence, the Polish state had neither time nor money to support the development of local ephemeral initiatives. As an alternative, it sought to attract foreign investment – from the US, Germany, Great Britain, Italy and France. Foreign companies brought their technologies and organisational solutions, which gradually suppressed and replaced the hitherto existing, domestic ephemeral organisations. The original construction of the CSW T-1 automobile, designed by Tadeusz Tański, is a notable example of this: its production, despite the novel solutions implemented in the design, was brough to a halt and replaced by the licensed production of the Fiat 508. The fate of our local ephemerals and – to some extent – that of foreign companies in Poland was sealed by the global financial crisis of 1929. First, it led to mass bankruptcies of Polish banks and enterprises. Then, in the second phase, it urged foreign companies operating in Poland to export their gains back to their centres. High profile trials – such as the Żyrardów affair – contributed to the mistrust against foreign investors. 12 12 J. Łazor, Kapitał francuski w Polsce międzywojennej. Stan badań i postulaty badawcze, “UR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences”, no. 1/2019. ↩︎

The third – and last – phase of organisation design in the interwar period bore the hallmarks of state interventionism. Weakness and disintegration of local private enterprise and the disillusionment and conflicts with foreign capital led to only one option: a shift towards state funded large projects and public ownership of enterprises. In 1936, the Polish government launched the implementation of such initiatives as the Central Industrial District or the port in Gdynia. The state created new enterprises in key industries: from the military to aerospace, automotive and electrotechnical. The state also took over private companies that went bankrupt, and assumed the place hitherto occupied by foreign capital. 13 13 J. Skodlarski, Historia gospodarcza, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2012. ↩︎ However, despite its twenty years of efforts, it is important to remember that even in 1938, Poland was still described (in a story published in “Life” magazine) as “a post-war state of fields” haunted by famine; where 40% of its citizens were illiterate and lived in constant fear of their neighbours from Germany and Russia.

The curse of discontinuity

When discussing the history of organisation design of the interwar period, we cannot omit its epilogue, i.e. World War 2, which, in a longer perspective, represented one of the steps in the deglobalisation process. During WW2, Polish institutions and industries were yet again taken over by the occupant and then destroyed during the war. This, however, did not mark the end of deglobalisation and its destructive effects on Polish organisations. In the post-war period, the world was divided into two camps, and Poland found itself under the influence of the Soviet Union. The communist regime implemented collectivisation and nationalisation. The owners of pre-war firms were eliminated and new organisational structures were introduced. In many cases, the war damage meant that reconstruction started from scratch, returning to the stage of the ephemeral and the improvised. In the 1980s, as the world entered a new era of globalisation, Poland was stuck in a system that disintegrated only a decade later. In 1989, the Polish economic system collapsed yet again, and new ephemerals emerged from its ashes – now functioning on the principles of a capitalist economy. Many years had to pass before they learned to benefit from the chances offered by globalisation.

This means that during one or two generations, the Polish state had experienced four crises (1918, 1939, 1945, 1989), after which a makeshift reconstruction was taken up. Jacek Kochanowicz, a prominent historian from the University of Warsaw, called this phenomenon ‘the curse of discontinuity’ and argued that the discontinuities in the process of economic development inhibited Poland’s long-term growth on three levels: 1) due to the instability and discontinuity of institutions; 2) due to the losses of capital and human resources; and 3) due to the shift of the Polish economy from the centre to the periphery of the European and global economy. 14 14 J. Kochanowicz, The curse of discontinuity: Poland’s economy in a global context, 1820-2000, “Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte/Economic History Yearbook”, no. 55/2014. ↩︎ Moreover, according to Kochanowicz, the state of discontinuity runs deeper in Polish history and includes the epochs of partitions, the Napoleonic wars and insurrections (the January Uprising in 1863/1864 and the November Uprising in 1830–1831). It can therefore be concluded that subsequent generations of Poles have been living in a state of permanent discontinuity for over 200 years, with each generation witnessing the collapse of their country’s socio-economic system at least once or twice in their lifetime and participating in its reconstruction. This conclusion is invaluable in the context of organisation design. After all, what motivation can an entrepreneur or citizen have to design an organisation in the long term and develop it patiently with the collapse of the system in 1989 still vividly present in their mind? In the following paragraph, I will try to summarise the conclusions and predictions regarding designing organisations in Poland in the coming years of the new deglobalisation.

Summary: designing organisations in Poland

The conclusions stemming from the history of deglobalisation in Poland are not optimistic. The awareness of the peripheral nature of our country, combined with the “curse of discontinuity” allow us to at least partially anticipate the mechanisms and consequences of the deglobalisation process that manifests itself in the form of the gradual deterioration of existing international relations, the outflow of foreign capital, a socio-economic collapse, the growth of statism and the nationalisation of the economy.

One could, of course, present several counterarguments. The Poland reborn in 1918 was in a totally different situation than the dynamically evolving, globalised Poland of the year 2024. The scale and the nature of the challenges that the government and the company owners faced in 1918 and today are entirely different. One might even be tempted to say that Poland has, in recent years, shifted towards the centre represented by such international institutions as the European Union or NATO. However, one cannot hide the fact that the trajectory of pre-war deglobalisation, as described above, is deceptively reminiscent of the trajectory of economic shifts in Poland after 1989. The boom in business activity in the early 1990s gave way to European integration and an influx of foreign investment at the beginning of the 21st century, before finally turning into the gradual renationalisation of recent years.

Facing these challenges, it is worth reflecting on the future of organisation design in Poland. In the current moment, two scenarios seem plausible – at least at first glance. In the first one, Poland can still integrate with the European centre. The organisations could be designed in such a way as to recover the credibility of state institutions, firms and companies ragged by the crises of the recent years, enhancing their resilience for the future. This would be done based on international regulations and EU law, and just as importantly, based on the financial resources of the European centre. In the second scenario, Poland can choose the road to deglobalisation and the peripheries, breaking up the current relations with the centre, leading to an outflow of capital; opting for its own solutions and, perhaps, opening up towards newly emerging centres such as China. In this case, the increasing number of challenges and crises related to climate change can lead to a breakdown in existing state institutions, and yet another surge in ephemeral organisations. It is important to remember that it will not be start-ups or organisations that shape social trends – it will be essential, self-help organisations and microenterprises. Deprived of support, these local ephemerals will be doomed to be taken over by new central organisations that would have access to capital and technology – thus, another cycle of deglobalisation would be completed.

Lastly, let us return to the old Polish saying: “makeshift is the most durable”. From the historical perspective, this statement does not mean that provisional organisations and solutions are capable of surviving any kind of shock. It can and should, be interpreted in as more sinister cautionary tale. That peripheral nature of our country and the curse of discontinuity mean that the long-term processes in Poland will inevitably end up in a breakdown of institutions and a return to ephemeral organisations, which make ‘makeshift’ is the most enduring element of our approach to designing organisations.

Bibliography:

Binda V., Colli A., Globalization: A Key Idea for Business and Society, Taylor & Francis, Abingdon-on-Thames 2024.

Braudel F., Wallerstein I., History and the social sciences: the longue durée, “Review (Fernand Braudel Center)”, Vol. 32, No. 2/2009, 171-203.

Colli A., Dynamics of international business: Comparative perspectives of firms, markets and entrepreneurship, Routledge, London and New York 2015.

Dziesięciolecie Polski odrodzonej: księga pamiątkowa, 1918-1928, Praca zbiorowa, „Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny”, Warszawa-Kraków 1929.

James H., The end of globalization: lessons from the Great Depression, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2009.

Jones G., Multinationals and global capitalism: From the nineteenth to the twenty first century, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005.

Kochanowicz J., The curse of discontinuity: Poland’s economy in a global context, 1820–2000. „Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte/Economic History Yearbook”, 55(1)/2014, 129–148.

Lanzara G. F., Ephemeral organizations in extreme environments: Emergence, strategy, extinction [I], „Journal of Management Studies”, 20(1)/1983, 71–95.

Łazor J., Kapitał francuski w Polsce międzywojennej. Stan badań i postulaty badawcze, „UR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences”, (1)/2019.

Skodlarski J., Historia gospodarcza. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2012.

Taleb N.N., Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder (Vol. 3), Random House Trade Paperbacks, Toronto 2014.

Wallerstein I., World-systems analysis: An introduction, Duke University Press, Durnham 2020.

Wańkowicz M., Ziele na kraterze, PAX, Warszawa 1957.

Weinberg G.L., Germany, Hitler, and World War II: essays in modern German and world history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge1996.

Zweig S., The World of Yesterday, Viking (University of Nebraska Press), Lincoln 1943.