Consciously resigning from comfort

Abstract

The common language of architecture is that of shelter and security. To this vocabulary, modernism added the concept of comfort. The twentieth-century house was meant to be a spacesuit, making the user independent of weather conditions and the natural world. By questioning the notion of comfort and opening up to the variability of seasons, humidity, temperature, and the presence of non-human species, we can better connect with the environment outside, experience the cycles of nature. Architecture that is open to ‘discomfort’ can be created by exploring traditional solutions from before the advent of electricity. ‘Analogue’ microclimatic solutions need to be thought of in the context of the biography of the planet, as well as expected climate disruption.

DOI: 10.48285/ASPWAW9788366835788PL

Katarzyna Roj interviews Małgorzata Kuciewicz and Simone De Iacobis

Katarzyna Roj: How do you understand the term: discomfort?

Małgorzata Kuciewicz: Our understanding results from our practice. When our sensitivity calibrated on natural phenomena in architecture, we started to ask ourselves why we were approaching it stereotypically, as if it was something that cut us off from nature. The language of architecture is commonly understood as a language of shelter and safety. However, if we think about threats that really affect us in the city, such as smog, then architecture will never be airtight like a spacesuit. At Centrala, we perceive architecture differently. For us, it is a layer where we negotiate our involvement with natural phenomena. We let go of the modernist myth of comfort, which suggests that architecture will provide us with an ideal bubble where we can control temperature, humidity and sunlight. Because if we let architecture separate us from atmospheric and natural phenomena, we then end up with a climate catastrophe

Of course, the notion of discomfort is problematic. We must remember that we use the term in the ‘global north’. While on an artistic residency in New Dehli, our conversation about discomfort took place on an entirely different level. It is political, which is why we cannot treat discomfort as opposition to comfort. What I mean by that is that we have to open ourselves to things we are not accustomed to. And this is something we are well capable of as animals. We can adapt to a chill, darkness or seasonal meals. We can also inhabit our environment while being more conscious about what we zone out and what we absorb. Perhaps this is why we like to compare this to seasonal cuisine – it is easy to translate it. Some people are ready not to eat supermarket strawberries in the winter – they focus on local deliveries and thus celebrate the passing of seasons. Why wouldn’t this happen in the context of dwellings? Let us remember that architecture connects us to the seasonal and daily weather cycles. Just like the clothes we wear, it could become another layer through which we are present in the world.

Simone De Iacobis: I am a fan of the saying that discomfort makes place for attentiveness. This is opposed to thoughtlessness, which contemporary architectural production urges us to believe in. We are being persuaded that architecture must be “all inclusive”, with a set temperature that remains the same all the time – namely 20 degrees Celsius, disregarding the current season. During summer, we cool down our apartments, and during winter, we heat them up with central heating. Generally, this suggests that we should ignore our surroundings. On the contrary, we propose to be attentive, despite the discomfort, and perhaps event thanks to it. Seasonal cuisine is a good example of this, and so is, for example, the red-blue chair by Gerrit Rietveld. When you sit on it, you feel your bones. You get back in touch with your own body and with the surroundings. Or when you lie down on a rocky surface while camping, and you can really feel your body. It is therefore a matter of architecture allowing you to reclaim the feeling of humidity, coolness and warmth of the atmosphere and enabling your body to react to it. Therefore, we can better connect with the world outside.

MK: Another good example is fashion. Clothes can provide a form for various rituals. We often point to the kimono, which restrains bodily movement to bows and squats. Through its rigidity and geometry, it underlines the beauty and softness of the body. In a similar way, we treat architecture as a coating for rituals. We can celebrate the flow of time by trimming our house. We water stones to provide the interior with humidity. We draw the curtains so that the chilly air can stay outside. It is an entirely different experience to controlling the home’s microclimate through a system of electronic remote controls and sensors. With electricity, we have lost our awareness of our dwellings. Thanks to those rituals, we have become conscious of certain laws of nature. But we usually remind ourselves about them when it is too late – when tree branches are already falling on our heads.

SDI: It just occurred to me, and I am not sure whether Malgorzata will agree with me, that architecture has the ambition to provide stability, which references the linear vision of evolution. But nature, on the other hand, develops in cycles. So, the architecture we propose should respond to cyclical regularity.

MK: The effort we make to furnish and accessorise a house translates into the comfort of feeling connected with natural cycles. Of course, we can only afford conscious dwelling when we do not feel hungry.

What you are saying is based on the premise that the natural cycles will follow one another in a specific order, whereas our scenarios of the future assume something entirely different: unpredictability, fluctuations, and disturbances.

MK: Therefore, we talk about design that needs to direct our perception of these changes. We can still cherish the seasonality – there will be some 15 cycles left of it ahead of us.

Is designing discomfort an arrière-garde of the world as we know it?

MK: We use this term, arrière-garde, to underline that now, more than ever, we should focus our attention on changes and transitions, sometimes those aimed backwards. And we should make use of the knowledge of past generations, which we keep losing access to nowadays. We can create new buildings and design them in such a way as to replicate a selected set of experiences of life before electrification. We can also move into old, traditional buildings that require a constant reconfiguration of their seasonal layers. To prepare the house for winter, one needs to apply additional windows, curtains or shutters in the event of blizzards.

SDI: Another example could be the “cold pantry” that was used instead of refrigerators. It was placed in the most protruding part of the house and used frost to cool foodstuffs.

MK: This is also related to the idea of seasonal cuisine because, in late winter, one would eat up all the stocks and preserves. Such a cold pantry or cupboard was present in numerous modernist housing blocks.

SDI: This is about the idea of storing coolness – a very beautiful concept on its own. Perhaps it was not researched enough, but we did encounter it several times. I could give examples from the house of Zofia and Oskar Hansen, e.g. an earthen cellar that stayed cool throughout the year. Or a small hill that was made to model the draught running through the house. We spotted another beautiful example of how to store coolness while living in a large apartment block in Ukraine: the earthen cellars were located amid tall blocks of flats and maintained by the inhabitants to store wine and vegetables. During the recent Venice Architecture Biennale, we discovered the Japanese tradition of preserving snow – it was mentioned in the installation by Kei Kaihoh called Melting Landscape. The architect presented a modern version of yukimuro – a traditional method of preserving snow and foodstuffs in the Japanese mountains. A little village called Yasuzuka, heavily affected by climate change, based its entire economy on yukimuro. The snow that was collected was used for a number of activities, including air conditioning of public buildings, agriculture, food production and the textile industry.

In Lower Silesia, accumulating coolness is still quite well known – it is our post-German building heritage. My parents, who live in an old villa, have a separate room that functions as a seasonal pantry. Luckily, the metabolism of the building was not damaged during the thermal modernisation and these old functions are still operational. On the other hand, however, there are instances of them being irrevocably destroyed. It’s like a pars pro toto in terms of the adaptation issue: we are not sure what we should adapt to if we do not know what we are missing.

MK: Arrière-garde relies precisely on our recognition of these old architectural solutions based on cyclicality and the laws of nature. We are surprised to discover how much was drawn by modernist architects from these old practices. Recently, during our stay at the Thugendhat Villa in Brno, we entered a special cold room: a walk-in closet for luxurious furs and coats. These garments were placed there for the summer so that the cold air protected them from clothes moths. And in the Stiassni Villa, the closets were made using mahogany and orange tree wood – their scent worked as an insect repellent and gave the clothes a pleasant smell. These subtleties were used by modernists instead of chemical agents. For us, this is a case of how the object interacts with the inhabitants of the space, e.g. through its scent. Not only humans – but in this case, also insects. There are many such cases – we learned about some while working on the Clothed Homeproject. E.g. the straw macramés that are now being laughed at, which used to be hung above sofa beds in tiny flats in apartment blocks: their sense was greater than just to pin a photo of your idol on it. They isolated from the cold walls and, just like the tatami mats, diffused the aroma of hay, elevating the quality of sleep. We think of such ‘analogue’ microclimatic solutions within the context of the planet’s biography and the anticipated climate catastrophe. The modernists knew how to direct the flow of convection currents and how to enhance the stream of cold and warm air, also at an urban level. We recently learnt that a cut in the topography of the site, e.g. in the form of what is known as a cold ditch – a ditch without water that runs parallel to a hill, directs the flow of cold air. Such knowledge proves very useful because we urgently need to amplify the air ventilation in our cities. This enables us to think about a city of microclimates – a mosaic that we can shape to avoid being burnt to death.

SDI: Our conversations with Jacek Damięcki shed light on a number of contexts regarding thermal contrasts. Regulating rivers and channels seems obvious in almost every city. As a result, watercourses are run through concrete and wetlands are shrinking. This is part of an attitude that references the notion of hygiene, the feeling of safety and city-wide comfort in general. But then, the role of natural rivers was also to provide cool air. Thinking about comfort within the city, let us remember that this concept resulted in such things as the urban heat island.

Now I understand that designing comfort reduces the subtleties of our perception, and that discomfort is neither the opposite of that nor a goal in its own right, but rather, it is a kind of protocol that brings us closer to the real world, with all its cycles and laws, whether physical or atmospheric. How do you perceive the political aspect of discomfort? Can it be justly distributed? Are you interested in individuals or…?

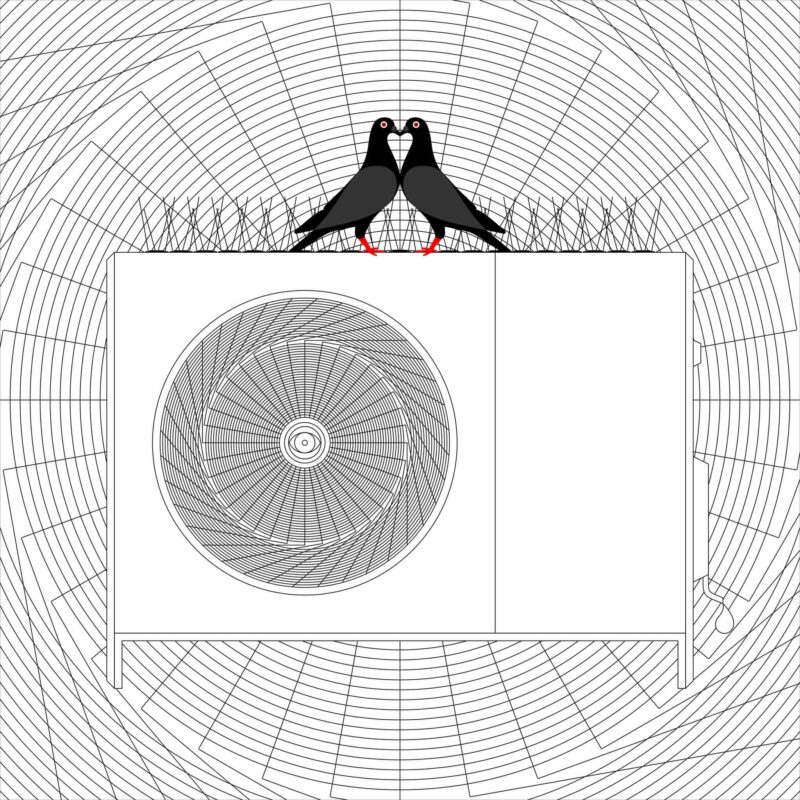

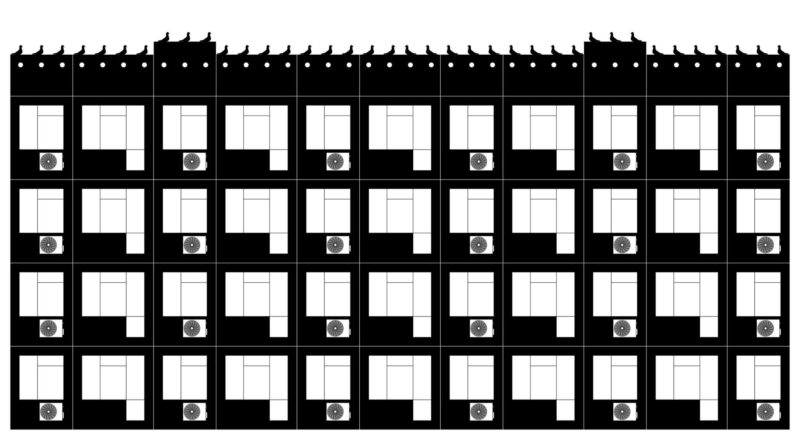

MK: No, we are interested in communities that inhabit a given city. Of course, we learn to think this way, celebrating our own relationships with the environment around us and observing the home in relation to the conditions outside. But we find ourselves drawn by the ways in which people inhabit the city – so, rather large scale. This is especially true in the context of an unexpected encounter with other inhabitants, e.g. animals. Here, we often bring up the example of curbing light pollution. We use too much light in order to feel safe, but this disrupts the daily cycles for both the animals and ourselves. And yet, we still need the night so that our biological clock can function well. We tend to cede the ecological cost of our actions and choices onto others. The heat from our air conditioning affects our neighbours’ microclimate. The heat we do not accept in our own interiors is literally tossed out. And just as the need to darkening down the cities is heard in the public debate, we are anticipating a discussion on how to regulate our negative impact on our neighbours’ microclimates so that people can understand that their comfort zone, which the need for a reduced temperature is part of, influences the thermal balance of neighbouring places.

SDI: In 2020, we carried out a project at the CSW Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, called Siedlisko Warszawa [Habitat Warsaw]. I must underline that the project had been planned before the change of the institution’s director. As part of that project, we conducted numerous conversations with experts, including the evolutionary biologist Marta Szulkin, who works at the University of Warsaw. We asked her what we could do to live in a bilateral agreement with urban animals. She replied that animals have very basic needs, quite similar to ours. For instance, they need a safe place to sleep. And even the most ordinary nooks and crannies in the facades of buildings, where small mammals, birds and insects hide, can be useful. It means that we do not really need to deprive ourselves of comfort when we invite animals to live with us. It would be sufficient to remodel the way we shape architecture.

MK: These conversations were very inspiring. I learned, for instance, that there is research conducted on the transitions in the colours of snail shells, which change in response to the rising temperatures in cities. The life cycle of tits, on the other hand, was disrupted because of shifts in phenological cycles. By adapting to local conditions, animals show us how these things change.

Did this translate to the idea of the Animal Quarter?

MK: We recently came to understand the idea of circular health when it turned out that the well-being of animals directly relates to ours. We need to take care of animals because we know from zoologists that they have nowhere to go. The non-city is equally industrialised and polluted. There is no wilderness anymore, just one large Anthropocene – a world reshaped by humans. Thus, we need to open ourselves to the presence of animals in cities, which, before Modernism, have already been a natural habitat for many species – until the time when sanitization as a concept implied our separation from them. Cities were then deprived of markets, butcheries etc. Modes of transportation also evolved, with horses no longer fulfilling this function. Nevertheless, for many people living out of town, living with animals still feels natural.

And all of this in the name of modern comfort.

MK: We do not understand the world of animals because of that. And for us, it is important to understand that, when we see numerous molehills in the garden, we can deduct that perhaps the fencing is too deep and the poor thing has no way out. We should be able to interpret the traces of animals, e.g. identify their faeces…

And when your think of the “animal world”, what do you actually have in mind?

MK: Wild animals. We started noticing reptiles and amphibians, which are especially endangered in cities. Birds, on the other hand, are popular – they are the victims of a “Bambi-effect”, they are simply likeable… unlike insects. We all have some kind of phobia against them.

Some animals are locked up in zoos. In one interview, you mentioned that we would soon be thinking of these in the same way we think of “human zoos” – people from non-urbanised areas, kept in ethnographic decorations, exposed to our gaze.

MK: It’s more than certain that there will one day be no more metropolitan zoological gardens in city centres. Conservation programmes are now part of academic laboratory research, totally unrelated to public entertainment. Keeping representatives of individual species in pairs, as in Noah’s Ark, is simply senseless. For instance, it takes an entire herd for hippos to start mating. In the zoo, there is usually a small number of them. We are unable to recreate the natural rules by which herds live wild. Additionally, Warsaw Zoo is special because it was created with the aim of reconstructing local fauna. Most other zoos represent a typically colonialist format based on exhibiting species from exotic, conquered territories. We also learned that exotic animals living in the Warsaw Zoo are already Varsovian, i.e. they underwent acclimatisation across several generations. A giraffe that lives here has little to do with its African counterpart since it learned to lick icicles. We assume that, by 2070, the zoo will either transform or even disappear. We calculated this based on the age of the animals. And now the question is: what to do with such a vast area? Should it be developed with the same kind of structures as everywhere else? These metropolitan zoos are located in attractive areas, usually connected to a waterway. In Warsaw, this is the pocket of the Vistula riverbed – a natural eco duct that animals migrate along. This could be a natural borough dedicated to the community of wild animals, but also a reception area for those who would migrate here due to the climate crisis. In this way, the place could “bio-react” when some migrations become problematic. Only through balancing the natural world are we able to gain a natural resilience before something terrible happens.

Such a borough could bolster many other functions, e.g. offering infrastructure that would support amphibians. There are not enough ponds for tadpoles. Despite being protected, they perish easily – they usually dwell in foundation pits. Providing them with a safe spot will not halt the investment. We also observed that the connection between the zoo and the city is tight: everything that is collected from urban greenery maintenance, such as mowed grass or raked foliage, can be used in the zoo. The zoo’s metabolism could also support the animals and organisms living freely. And here we come back to the motif of discomfort and the need to normalise the “dirty” processes in the city: destruction, disintegration and decay, which were all expelled from the city.

SDI: Here, again, the motif of nature’s circularity comes back. When we remove fallen trees from the city, we do not allow fungi to take over and transform the organic matter, enabling the regeneration of the ecosystem. This process can be observed in natural forests. The city is not in favour of such processes.

MK: Since the process of decay is interrupted by the cutting of the tree, we are slowly running out of holes and cavities, which are natural dwelling options for many birds and rodents. We recently made a drawing in which an old branch with holes was suspended from a healthy tree. If such things were possible, we wouldn’t need to hang plastic or ceramic birdhouses. But then again, we would require a place in the city where the processes of decay are allowed and supported.

SDI: There is no formula for the Animal Borough – it’s rather our intuition. But, as Malgorzata mentioned, the zoo is a large area connected to an ecological corridor. This could be a place where wilderness borders the urban world. It’s an ecoton – an area where two neighbouring ecosystems merge. Because a city is also a kind of an ecosystem, albeit an anthropogenic one. We imagine it as an area of negotiation between these two worlds and we know that it will be largely based on discomfort. But we would also like to revisit this etiological myth of the origins of the Warsaw Zoo: that it was created to serve the wilderness rather than humans. The whole infrastructure that could emerge there would support and nurture these “unclean” natural processes.

MK: An important element of this project would be a Centre for Inter-Species Relations, because one of the reasons why we feel uncomfortable in contact with animals is because we are unable to understand them. One of the things we could learn there would be to recognise animal traces, so that we pass by each other more consciously.

SDI: We mentioned the cycle of natural seasons, but I would also like to mention the cycle of day and night, as this is the reason we miss out on the encounter with numerous animals. Simply put, our biological clock is entirely different. The majority of free-living animals are most active at night or during this third, crepuscular phase – at dusk and dawn. Recognising our coexistence in the city is key: we are simply active at different moments.

MK: This reminds me of what is known as a “bird clock”, i.e. the ability to tell the time after waking up, based on which birds we hear outside the window. But let me come back to the dirty processes again. When we think of architecture in cities, we rather refer to our visual experience – shapes and colours. However, the animal world is different because other senses are much more important than sight, and at the same time, their relation to the ground is different, too. It is important for us to shift from thinking about a sight-oriented inhabitant that walks straight up, and to focus more on textural surfaces, the intensity of smells, the different air pressures and the feeling of windward vs leeward. Animals navigate mostly thanks to finding their way in these natural phenomena. We can learn that from them. The most difficult part is the change of perspective. Design for animals is not only about creating drinkers and feedlots, it also encompasses projects that don’t affect their lives at all, moreover those that create microclimates that may be uncomfortable for humans but are needed by animals, e.g. dark and humid burrows. Design for animals can also be expressed in the way we devise underground infrastructure – understanding its vibrations and the fact that it will disrupt the daily life of all creatures living underground.

I am fascinated by such a vision. What should we do to approach it?

MK: For me, a mindfulness course was helpful. I gave up my air-con, turned down the heating, took my curtains down and observed the nuances. I wear a warm sweater indoors and, during the night, I keep an eye mask on hand whenever I need some more sleep after first waking up. I do not force my own rhythm onto plants. In our office, we made friends with spiders, we don’t panic when we see an ant or a fly and we negotiate with them through, e.g. the system of snack packaging. We cultivate a tiny water garden and learn from our mistakes. We go out more often, we smell, we listen and we touch. We observe kids and their ability to admire the world around them. Negotiating the borders of one’s own comfort inspires us to discover new architectural topics. We are open to discussing projects related to amplifying nature with architecture, our research into urban wetlands, hydrobotanics, and the potential to build houses or apartments with ponds on their balconies or roofs. We would be happy to engage in creating experimental testing grounds and other areas of unexpected encounters.