Urban Contexts For A Sustainable Development Of Space

Abstract

In the face of many contemporary challenges, including progressive urbanization and the climate crisis it is necessary to revise urgently the directions of urban development. The shaping of urban spaces is of particular importance. Spatial change provides a long-term strategy for urban development. It requires abandoning the existing status quo of urban planning, which has been detrimental to cities and their inhabitants. Spatial planning of contemporary cities should include the category of responsibility, which creates the perspective of commons. The goal is to build pro-social, vital and resilient urban spaces. “Urban designers” can stimulate spatial processes that are important both from the perspective of the local communities involved, as well as in the context of global changes. They can shape a new urban culture – one that is socially and ecologically responsible. The paper indicates the axis and key practices of the postulated changes.

DOI: 10.48285/ASPWAW9788366835788PL

Introduction

There is no doubt that urban space is becoming increasingly important. The multifaceted debate on its quality, design, accessibility and functions has various contexts. Recently, several topics have been especially resonant. These include:

- the importance of the natural environment and the direction towards climate neutrality,

- locality,

- treating space as a shared good, and

- cooperation and co-creation.

These subjects, essential in the discourse on space, stem from a need to take urgent action towards sustainabledevelopment. The term “sustainable space” is rooted in the paradigm of sustainable development. “Shaping sustainable space is based on a design philosophy where the natural environment, man and the effects of his actions function in a mutual symbiosis.” 1 1 A. Sobol, Wpływ przestrzeni wspólnych na rozwój miast, [in:] Przemiany przestrzeni publicznej miast, ed. I. Rącka, PWSZ, Kalisz 2017, p. 64. ↩︎

Urban space refers to the urbanized environment and is a very complex concept. It includes everything that surrounds us and is a product of both human activity and natural origin. It is also a sphere of numerous interactions, both passive and active, intended and spontaneous. A holistic approach to space is a key element inscribed in building a sustainable urban development. Reading the urban composition in a systemic way requires taking a full perspective, both subjective and objective. This approach is also informed by the idea of multisensuality, a term introduced by Joseph Rykwert 2 2 J. Rykwert, Pokusa miejsca, Przeszłość i przyszłość miast, Międzynarodowe Centrum Kultury, Kraków 2013. [Original English edition: J. Rykwert, The Seduction of Place: The History and Future of Cities, Pantheon Books, New York 2000 – KCA]. ↩︎. The eclecticism inherent in multisensuality is useful when defining the characteristics of contemporary cities, by expressing a need for urban entities to meet the increasingly diverse expectations and attitudes of the inhabitants. The multisensuality of urban spaces can be shaped by various factors, among which nature and urban design play a special role.

The importance of the natural environment and the direction towards climate neutrality

Our increasing awareness of the negative effects of human activity and the alarming predictions regarding climate catastrophe have resulted in a revision of urban development policies. The reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 3 3 Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, red. Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri i L.A. Meyer, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Geneva 2015, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf, accessed 16 June 2022. ↩︎), published since 1990, have been giving an ever-broader image of the situation. Taking the global scale into account, they draw attention to the shrinking areas that can be qualified as habitable. At the same time, the urbanisation trend continues; it is estimated that by 2050, the percentage of people living in cities will increase to 68% of the global population. Climate change may cause mass migrations in search of a ‘living space’. The forecasts of the World Bank indicate that by 2050, 143m people will become climate migrants or climate refugees 4 4 C. Raleigh, L. Jordan, I. Salehyan, Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Migration and Conflict, The World Bank, Washington 2008. ↩︎. In the face of growing environmental issues, including climate change, the co-dependence of our existence on a spatially limited planet is becoming increasingly clear.

The revision of urban development requires that the symbiosis of man and nature be reinstated. This approach towards urban design and landscape architecture was uttered by Christopher Alexander:

“[…] when you build a thing, you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent and more whole; and the thing which you make takes its place in the web of nature, as you make it.” 5 5 Ch. Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King, S. Angel, Język wzorców. Miasta, budynki, konstrukcja, przeł. A. Kaczanowska, K. Maliszewska, M. Trzebiatowska, GWP, Gdańsk 2008, p. 31 [Original quote from: Ch. Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King, S. Angel, A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction, Oxford University Press, New York 1977, p. xiii – KCA]. ↩︎

The environmental context is inscribed in the need for frugality in spatial design. This is understood both in the context of creating a dense urban structure as well as using spaces that are already developed – which includes the latter’s revitalisation and adaptation to new functions. These actions, described as urban space recycling, are critical in cities and urbanised areas where there is extreme pressure to develop the hitherto “empty” spaces, and green areas in particular. In order to counteract these processes, it is vital to inventorise and repurpose areas that are developed but underused, including post-industrial sites, building gaps and vacant lots. The recycling of space is one of the processes that stimulate positive action directed towards urban development and foster the desired phenomena and processes related to climate change adaptation, reduction of the city’s carbon footprint and increasing the values of urban space. Restoring disused infrastructure and adapting it for socially desirable purposes is also a kind of spatial recycling. One of the best-known examples of such an initiative is the High Line Park in New York, developed on top of a structure of an unused railway by James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and landscape architect Piet Oudolf.

The frugality of urban design not only relates to urban space but also to all the elements that are introduced into it – i.e. buildings or ‘street furniture’. An awareness of the environmental impact of all components of the space is linked to the consideration of the ecological footprint in the life cycle of individual products and services. This trend, accentuating the reduction of the negative environmental impact and promoting moderation in all instances, is described as frugal innovation. This term, in turn, is linked with the idea of bricolage, a term sourced from the field of fine arts that denotes spontaneous creation based on readily available resources. The simplicity of forms and materials, attention to quality and user accessibility are all inscribed in the context of frugality, as is the aspect of local provenance, which is also important here.

Locality

Emphasising the importance of caring for the environment, the significance of ecosystemic interrelationships and the need to have a socialised spatial planning and design process are all embedded in the local urban development context.

It is important to note that the global scale mentioned above is generated by the sum of millions of activities conducted on a regional and, most importantly, local level. An association with the well-known slogan: “Think globally, act locally” is most legitimate in this case. This motto, attributed to the Scottish thinker Patrick Geddes who was active at the turn of the 20th century, defines an interdisciplinary approach to urban planning. Geddes’ vanguard understanding of the environmental, social, and economic interdependencies that influence the shaping of cities is also still accurate today 6 6 See: P. Boardman, The worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, town planner, re-educator, peace-warrior, Routledge & K. Paul, London, Boston 1978. ↩︎.

The measure of locality is determined by designing “on a human scale”. Geddes is also named a godfather of this approach. Among his followers who implemented his ideas in the 20th century were Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl. Jacobs, known to have run numerous battles with architects and urban planners regarding the “familiarity” of the Manhattan area, confronted herself with the premise that “city people seek the sight of emptiness, obvious order and quiet.” 7 7 J. Jacobs, Śmierć i życie wielkich miast Ameryki, transl. Ł. Mojsak, Fundacja Centrum Architektury, Warsaw 2014, p. 55. [Original quote: J. Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Books, Random House, New York 1992, p. 37, http://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf, accessed: 11 May 2022]. ↩︎ According to her, such an approach eliminated, in the process of town planning, the elements of untamed nature or the activity of individual citizens, regarded as unpredictable and “appropriating” the urban space.

In Gehl’s projects, the “human scale” has, in turn, a multifaceted character. It relates, on the one hand, to a direct meaning of scale, and on the other – to local conditions 8 8 J. Gehl, Miasta dla ludzi [Cities for People], transl. S. Nogalski, Wydawnictwo RAM, Kraków 2017; J. Gehl, Życie między budynkami. Użytkowanie przestrzeni publicznych [Life Between Buildings], transl. M.A. Urbańska, Wydawnictwo RAM, Kraków 2009. ↩︎. From the standpoint of a human scale, the city space is seen from a local perspective. What is important is thus what the inhabitant can grasp in his/her everyday reality. Locality “sewn into” our everyday functioning determines that we care about it. Reducing waste, caring about the aesthetics and our relations with other inhabitants will, in the long term, provide good living conditions.

Space understood as a place for a dialogue of the local community was accentuated in the works by Clarence Perry from the 1920s onwards. In one of his projects, Perry underlined the significance of local communities in his urban development schemes for a so-called social unit of about 10,000 inhabitants. His ideas were later adapted in the frame of the New Urbanism movement developed in the 1970s. One of the leaders of this movement, the Luxembourg-based architect Leon Krier, underlined the need to counter alienation and the anonymity of the inhabitants in the development of cities. The reconstruction of cities, perceived as a well-functioning social tissue, is fundamental to building a proper relationship with the place, the local nature and our care for the town. This is what sets out an awareness of local identity.

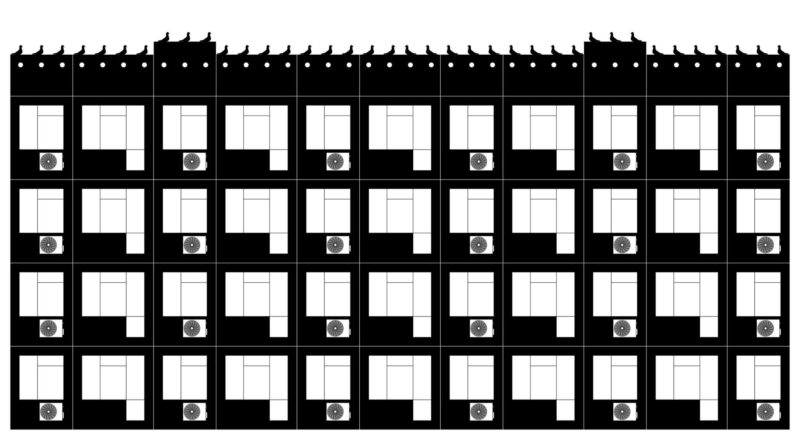

An important megatrend that results in breaking the ties between cities and locality is the commercialisation of space. Global corporations introduce their products and services in city spaces around the world, leading to mass standardisation and the transformation of organisational structures of local economies and social processes. The consequences also include increasing pressure on the natural environment.

Spatial politics, as well as designers and their sensitivity, should consider the specific conditions of the place: geographical location, climatic and environmental conditions, history, culture and, above all, the needs of the local community. Only then will the project have a chance to be welcomed and inscribe itself in the local contexts. Thus, it can become authentic.

Urban space as commons

The quality of life of people living in cities is largely defined by the quality of the space where this urban life takes place. Despite having different functions, ownership relations and characteristics, these spaces, as interacted with and observed by various users, possess the traits of communal spaces.

Common goods are defined as goods that, regardless of their ownership status (private or public), have a key significance in understanding the needs relevant to the rights of all residents 9 9 UNESCO, Rethinking education. Towards a global common good?, Paris 2015, https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/RethinkingEducation.pdf, accessed 16 June 2022. ↩︎. Treating urban space as a common good – as urban commons/municipal common goods – has manifold consequences. It also points to the need to shape it while including the perspective of all its users.

It should be stressed that urban space is a collective work. Its egalitarian character should be filled with egalitarian content. This requires dialogue between the creative milieu – urban planners, urban designers and architects – and the inhabitants. The awareness of the citizens’ rights to the city should become an inherent element of the former’s practice.

“The egalitarianism of the city is fulfilled through accessibility, the possibility of common usage and the inclusive character of the space. It is a value in its own right, achieving which should become a common task for governments and the users of specific spaces, whereas urban design should only be a tool to achieve this goal.” 10 10 M. Piłat-Borcuch, Design, designer i metamorfozy miejskie. Studium socjologiczne, Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa 2017, p. 227. ↩︎

The possibility of common usage is crucial for common spaces. However, cities are, more often than not, being deprived of public space – common and free space for everyone, and especially the green areas, which are eliminated on behalf of private investors, whose interests often stand in opposition to the general public interest. The commercialisation of space and the forces of the market have the final say and thus win over the fight for the rights to the city 11 11 J. Sepioł, Uwagi o urbanistyce i architekturze III RP, [in:] Miasto na plus. Eseje o polskich przestrzeniach miejskich, Wysoki Zamek, Kraków 2018. ↩︎. Sustainable development requires proper prioritisation – the interest of the customer, including the “sacred right to property”, should not stand above the interest of the entire community, and the common good should be guaranteed by law and by the mechanisms of urban planning.

The processes of privatisation and commercialisation that intensify within cities result in a situation where an increasing number of spaces become spaces of consumption, often excluding those who cannot financially afford to become their users. These spaces often simulate being open and publicly available. A parcellation of space by private investors results in a lessening of interest in and care for the common space. This often leads to deepening underinvestment and neglect.

Additionally, it should be noted that urban space reveals a lot about its inhabitants, their lifestyles, the condition of democracy, social relations, the significance of culture and the ecological consciousness. In short – urban space creates an image of us as a society. After all, cities are made by humans and reflect civilisational changes.

Cooperation, co-creation…

One can agree with the thesis that cities were created as an idea of “public space where people live together, consider and decide together on everything that touches upon their common interests.” 12 12 K. Nawratek, Miasto jako idea polityczna, Wydawnictwo Ha!art, Kraków 2008, p. 26. ↩︎ However, contemporary urban planning is far from this idea.

Participatory design can be implemented in urban planning and spatial design. It implies a revision of viewing space as merely an object of urban planning. Inscribed in the socialisation of the planning process, space is understood as a common good. It indicates a strong inclusion of the attribute of communality in urban planning. This refers particularly to questions such as co-creation, collaboration and co-responsibility for the development of cities.

Therefore, our shaping of cities should not be an effect of the materialisation of visions by city planners, designers and architects. On the contrary: it should be the users – the inhabitants of cities who become subjects in the design process. Space as the common good requires that the voice of various users, especially the local community, is heard.

A valuable direction regarding the recycling of space is to introduce deficit public social functions and services into the reclaimed space. A good idea would be to adapt these spaces for civic activities, social economy initiatives or for the development of micro-enterprises in the creative industries. The process of shaping these spaces should be carried out in a socialised formula. Such places could become a catalyst for positive social and economic transitions.

The initiatives towards shaping sustainable spaces within cities often have a bottom-up character; they are undertaken by the residents themselves. This perspective indicates that the space can be a vehicle for socially engaged content. Residents’ initiatives not only have the power to animate spaces but also add a “healing” value to the local community. These values stem, on the one hand, from the process of co-creation itself, which helps integrate the inhabitants and rebuild relationships and mutual trust between members of the local community. On the other hand, it can even liquidate the barriers of the hitherto existing structure, composition and functions of the space, creating obstacles between people. A good example of creating and dismantling barriers is fencing – or the lack of it; its character and size. Fences can appear as ‘friendly’ or ‘hostile’. Moreover, when implementing fencing, the urban space can become subject to segregation and stigmatisation on the basis of economic status, race, etc.

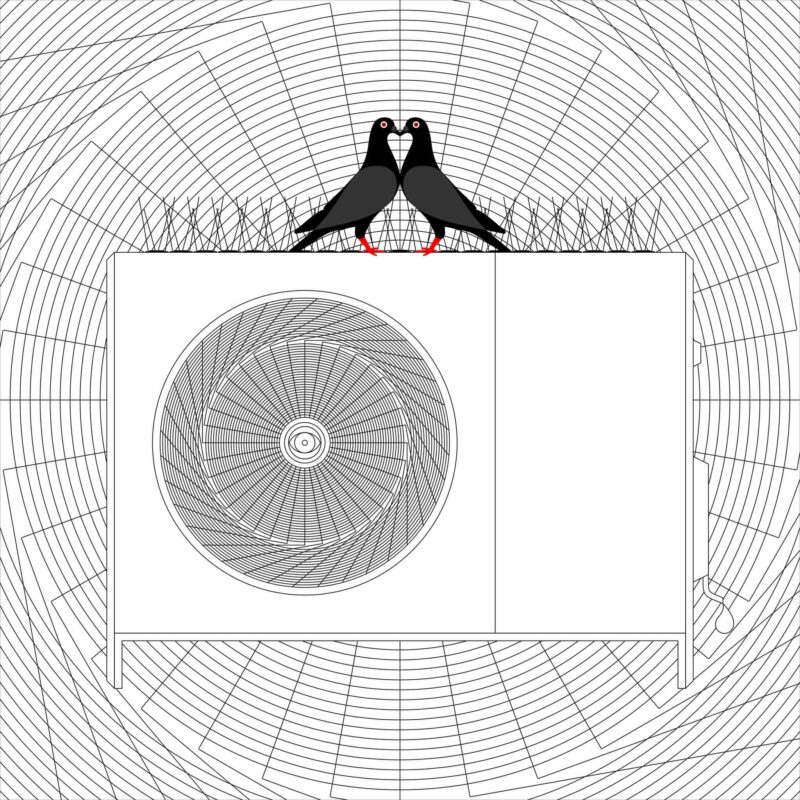

Nowadays, there are multiple instances of actions that exclude urban space. These are most often associated with the fragmentation of space due to the parcellation and enclosure of private spaces. On a symbolic level, fencing and even guards point to the disintegration of social bonds. “Ghettoisation” is a trend that is detrimental to cities, especially in the central areas. It can take quite sophisticated forms. The need for safety, order and cleanliness can implicitly support a conscious exclusion of others. As an example, elements of street furniture are introduced into the urban space with the intention to repel certain individuals who are unwanted from the perspective of the majority group.

In effect, narrow and uncomfortable benches or “unfriendly” bus stop shelters become weapons in the fight against homeless people or anyone suffering from illnesses or addictions. As a result, this practice, dubbed as the architecture of poverty, discourages everyone from actively using it and, on top of all that, does not fight the issue of homelessness. A contradictory trend is to connect commercial projects with opening up on the “public addressee”, and co-investing in the neighbouring public space. One of the examples includes the development of Plac Europejski (Europe Square) in Warsaw.

More systemic approaches touch upon segregation and the division of inhabitants into “better” and “worse” social groups. Such practices, known as redlining, were widely applied in the US and Canada. A policy of racial discrimination was embedded in American city-planning. Boroughs were redlined according to their attractiveness to private investors, but also with regard to public policy objectives. The “worse” boroughs invest less in technical infrastructure; local governments tended not to build any libraries or museums, they did not create parks and they tended not to equip schools. The results of this segregational project, conducted in the boroughs of many American cities mainly between 1933–1978, are still visible today 13 13 A.M. Perry, D. Harshbarger, America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them, “Brookings”, https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/, accessed 16 June 2022. ↩︎. In Chicago, there are still a few boroughs that suffer from that underinvestment.

Projects that reconstruct the broken relationships between various parts of the city, and especially between people, should engage the local community. The Sweet Water Foundation is an NGO that, with the support of local activists, architects, designers and artists, helps local communities in regenerating the boroughs that have been marginalised over decades. It creates civic integration centres, community gardens, common rooms and repair cafés where the value of social engagement has the power to repair the entire district.

Education, especially in neglected neighbourhoods, is also bestowed with this power. The Open-Air-Library in Salbke, one of the districts of Magdeburg, provides an example of a recycling of space that merges education, ecology and communal undertakings 14 14 KARO*, A. Heuer, S. Rettich, B. Hafermalz, Architektur+Netzwerk, S. Eling-Saalmann, Open-Air-Library Magdeburg, Germany, 2004-2009, https://www.architonic.com/en/project/karo-open-air-library-magdeburg/5100461, accessed 16 June 2022. ↩︎. At the turn of the 20th century, the borough faced severe social and economic issues: 80% of the buildings were vacant and the unemployment rate reached 20%. In 2005, a collaboration between the local government, architects and inhabitants led to the creation of an open-air library in one of the main squares of the district. The premises were initially built from recycled beer crates donated by the inhabitants, who also provided the first 10 000 books. This volume continues to be increased by the users. After some time, the crate structure was replaced by a building made using elements from a dismantled shopping centre. The project is, in its essence, socially engaged and the space of the library is used as a venue for local activities and events.

Space has the power to be socially influential. The space co-created by its inhabitants has a greater potential to become “animated”, i.e. used and being cared for. Co-creation enhances the context of space as a common good.

Conclusion

From global issues, such as the prognosis of an increase in the number of climate migrants mentioned at the beginning, to the question of planning individual cities, the road is seemingly long. However, with more than half of the global population living in urban spaces, the ways in which such spaces are developed are globally determined by several factors. The confrontation with the scale of these interrelationships and interdependencies seems increasingly inevitable.

The cumulation of the negative aspects of urban planning is most visible in cities. At the same time, a sustainable space becomes an increasingly desirable asset. In the face of the challenges that occur, an integral approach to urban design, encompassing the ecological, environmental, social and aesthetic aspects as well as balancing the global-local relations, is recommended.

The category of responsibility should be inscribed in the planning of contemporary cities. This requires effort from all participants of the urban space and abandoning the short-sighted perspective of private interest. Apart from that, it is necessary to perceive space as a common good. Here, the key role is played by urbanists, architects and designers who plan and furnish the space. Their knowledge and awareness of the complexity of processes and elements of urban space design should become a “safety valve” for urban investments. Their authority should validate the questioning of the existing rules of the game and the dissent against the realisations that oppose the social, ecological or aesthetic contexts. “Urban designers” can stimulate spatial processes that are important both from the perspective of the local communities involved, as well as in the context of global changes. They can shape a new urban culture – one that is socially and ecologically responsible. Additionally, introducing participatory design to urban management leads to the subjectification of spatial decision-making and to the implementation of the characteristics of the common good.

The state of urban spaces is a lens through which one perceives the conditions of living on Earth. It is a testimony to how we understand the common good. A revision of existing directions in which cities have been developing shows us the need to prioritise values such as authenticity, community and nature. The goal is to build pro-social, vital and resilient urban spaces. Spatial change provides a long-term strategy for urban development. It requires abandoning the existing status quo of urban planning, which has been detrimental to cities and their inhabitants. A revival of urban space will be a symbolic resurrection of our planet.

Bibliography:

Ch. Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King, S. Angel, Język wzorców. Miasta, budynki, konstrukcja, transl. A. Kaczanowska, K. Maliszewska, M. Trzebiatowska, GWP, Gdańsk 2008. [Ch. Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King, S. Angel, A Pattern Language. Towns, Buildings, Construction, Oxford University Press, New York 1977].

Boardman, The worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, town planner, re-educator, peace-warrior, Routledge & K. Paul, London, Boston 1978.

Gehl, Miasta dla ludzi [Cities for People], transl. S. Nogalski, Wydawnictwo RAM, Kraków 2017.

Gehl, Życie między budynkami. Użytkowanie przestrzeni publicznych, [Life Between Buildings], transl. M.A. Urbańska, Wydawnictwo RAM, Kraków 2009.

Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, red. Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Geneva 2015, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf, accessed 16 June 2022.

Jacobs, Śmierć i życie wielkich miast Ameryki, transl. Ł. Mojsak, Fundacja Centrum Architektury, Warszawa 2014 [J. Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Books, Random Huose, New York 1992, http://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf, accessed 11 May 2022].

Nawratek, Miasto jako idea polityczna, Wydawnictwo Ha!art, Kraków 2008.

KARO*, A. Heuer, S. Rettich, B. Hafermalz, Architektur+Netzwerk, S. Eling-Saalmann, Open-Air-Library Magdeburg, Germany, 2004-2009, https://www.architonic.com/en/project/karo-open-air-library-magdeburg/5100461, accessed 16 June 2022.

A.M. Perry, D. Harshbarger, America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them, “Brookings”, https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/,accessed 16 June 2022.

Piłat-Borcuch, Design, designer i metamorfozy miejskie. Studium socjologiczne, Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa 2017.

Raleigh, L. Jordan, I. Salehyan, Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Migration and Conflict, The World Bank, Washington 2008.

Rykwert, Pokusa miejsca, Przeszłość i przyszłość miast, Międzynarodowe Centrum Kultury, Kraków 2013. [J. Rykwert, The Seduction of Place: The History and Future of Cities, Pantheon Books, New York 2000].

Sepioł J., Uwagi o urbanistyce i architekturze III RP, [in:] Miasto na plus. Eseje o polskich przestrzeniach miejskich, Wysoki Zamek, Kraków 2018.

Sobol, Wpływ przestrzeni wspólnych na rozwój miast, [in:] Przemiany przestrzeni publicznej miast, ed. I. Rącka, PWSZ, Kalisz 2017.

Sweet Water Foundation, https://www.sweetwaterfoundation.com/commonwealth, accessed 16 June 2022.

UNESCO, Rethinking education. Towards a global common good?, Paris 2015, https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/RethinkingEducation.pdf, accessed 16 June 2022.